Meaning of Life – Recent Scientific Paradigms

In the first part of my series of articles investigating the overarching philosophical concept of the “meaning of life“, we discussed the challenges around its definition and started looking into the changes in the views that have occurred over the centuries. Here we will further explore the factors that have led to the massive popularisation of this subject in recent decades, and will finally turn to some of the predominant views and paradigms around it.

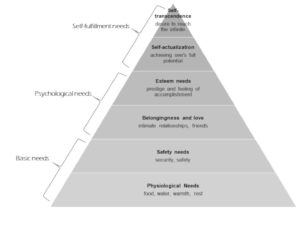

One of the less obvious considerations as to the scale that the matter of purpose of life has taken unveils itself once we consider Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs’ pyramid (see picture) and its main principles:

- needs at the bottom are the more fundamental and basic ones, while the “higher” needs, such as the need for self-actualisation and self-transcendence, rest at the top;

- the most basic level of needs must be met before the individual will strongly desire (or focus motivation upon) the secondary or higher-level needs.

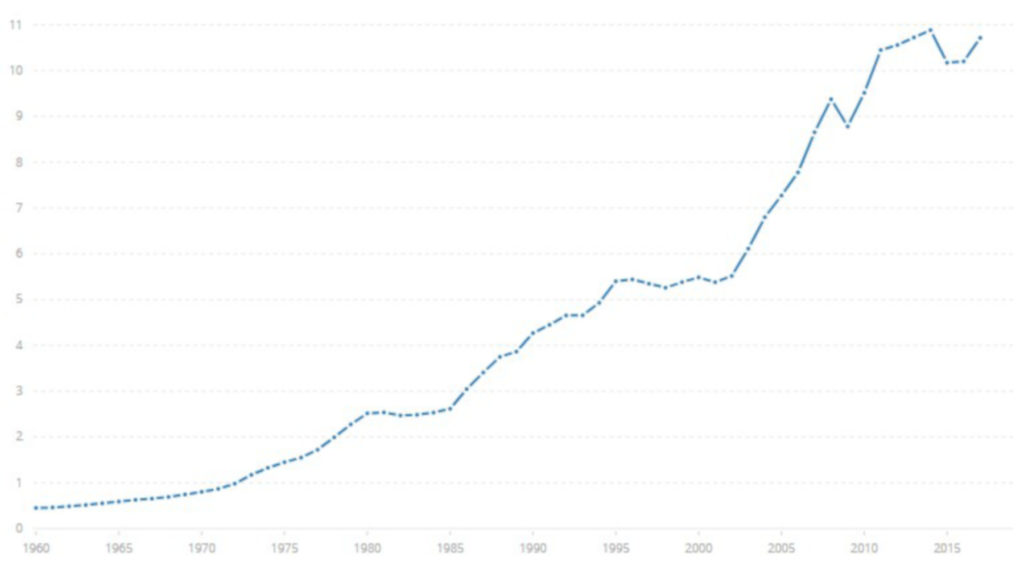

If we then presume that the quest for meaning in life falls within the higher levels of the needs’ hierarchy presented above, it may be possible to assume that the individual would have enough energy and motivation to deeply pursue this investigation of the meaning once his fundamental needs are met. Would it be possible then to find a correlation between the popularisation of the notion of “purpose in life” and the general level of well-being in modern society? It is a fact that, from a historical perspective, we are living in the age of abundance:

The GDP per capita, as well as consumer spending, have been growing steadily in the last half a century (see graph below). Do we, as a society, simply have more motivation and energy these days to have an existential discussion than we used to have because our fundamental needs are generally more satisfied nowadays?

Now that we’ve touched upon the factors which have led to the current state of the discussion around the meaning of life, let’s look into a few of the current views on what one’s life meaning could be as well as what the purpose of life in the universe as a whole is.

As the rational mind picks up the slack from the esoteric mind in an attempt to re-invent the meaning and purpose of life, dozens of new paradigms emerge in a struggle to find some logic behind life’s existence; while society adopts various “causes” like WWF, Peta, and the like, looks to art and creativity, in search of a similar emotional attachment and equivalence to that of the religious belief.

Some of the developments in conventional science, as well as cosmology, seem to fall in support of the latter view. According to physicist, Lawrence Krauss, in his latest book, “The Greatest Story Ever Told … So Far”(2017), the fact that we evolved on this planet is just a “cosmic accident” (Price, 2017). Renowned evolutionary biologist, Richard Dawkins, in “The Blind Watchmaker” (1986) argues that evolutionary processes, such as reproduction, mutation, and selection are analogous to a blind watchmaker, and in no way guided by an external “designer”.

However, the seemingly improbable “bio-friendliness” 1 of our universe suggests that “the universe were ‘designed’, against the odds, for the function of enabling life to emerge” (Price, 2017). This latter observation forms a part of the recently developed scientific line of thinking amongst theoretical physicists, called CNS (Cosmological Natural Selection), proposing that evolutionary theories might go far beyond explaining the features of life on Earth and, can, indeed, be a key to explaining the features of the universe and, specifically, the existence of intelligent life.

CNS is based on an idea that we live in the multiverse of self-replicating universes.2 It is in the mechanism of replication that the further discussion lies: Lee Smolin argues that it is through black holes that the replication occurs3, while a different theory suggests that intelligent life could also be a mechanism of replication. One of the early adopters of this theory, Edward Harrison, summarises the concept and gives a new spin to the “meaning of life” quest:

Not inconceivably, the goal in the evolution of intelligence is the creation of universes that foster intelligence.4

Conventional sciences such as cosmology, mathematics, and physics try to explain life as a phenomenon and its purpose in the universal arrangement, as well as the role of humans as a life form in all of this. What about the purpose of one individual human life? Is there any purpose to it at all? This is where we look to philosophy’s greatest minds in search of the answers, and this is what we will do in the following part of this series.

_

1 the observation that many laws and parameters of the universe seem precisely adjusted to enable the evolution of life (Price, 2017)

2 To dive deeper into the concept of multiverse consider reading David Deutsch and, specifically, his book called “The Fabric of Reality”.

3 Smolin, L. (1997). The Life of the Cosmos. Oxford University Press

4 Harrison, E. R. (1995). The natural selection of universes containing intelligent life. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 36: 193-203