Life in a Refugee Camp

You can just imagine it. You can never feel it. The feeling of being displaced, of insecurity, of oppression, of fear; the feeling of living with hopes and hopelessness at the same time; the feeling of living with death. It is my home but still it is not. I cannot let it be. I feel at home here but yet I don’t feel at home.

I tried to understand what he was trying to tell me. I wanted him to tell me more. He was born in a refugee camp. I was having this serious conversation with a Palestinian guy, when the bus screeched to a halt. And we could hear the coordinator shouting “yalla yalla”. It is a common expression in Arabic meaning, “come on”, “let’s get going” or “hurry up”. To be honest, by the time the trip was drawing to an end, we could no longer hear these two words “yalla yalla”. Because whenever we would start to enjoy a place, we would hear the coordinators shouting the words, “yalla yalla; time to leave”.

We stepped out of the bus. We were in the Al-Jalazone refugee camp. It is seven kilometers from Ramallah. Our coordinator gave us some instructions regarding what to do and what not to do.

We were also instructed not to leave the group at any time, as refugee camps are like a maze where you could easily get lost. It could be really difficult for someone who gets lost to locate his or her group because of the language barrier.

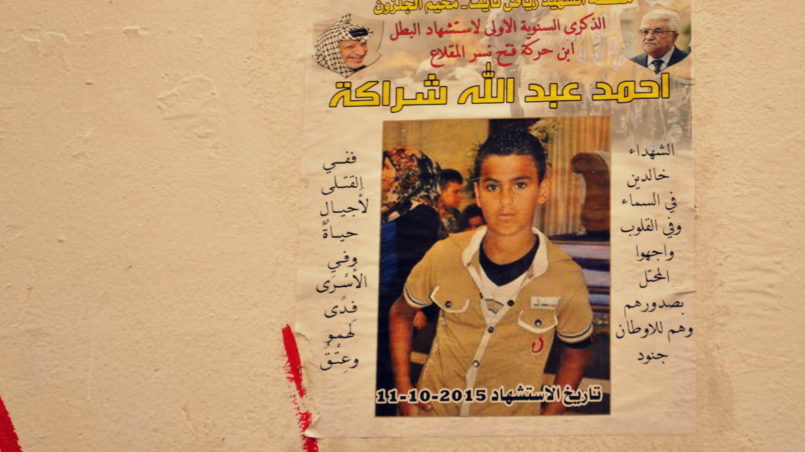

I started to walk around, taking photos of the walls full of graffiti, of billboards, of narrow alleys and everything that attracted my attention. The walls were painted with pictures and full of posters of martyrs: those killed by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), those killed during demonstrations and confrontations with Israeli soldiers, and those who chose death over life to liberate their land. The faces of martyrs were accompanied by a short paragraph, describing their age, the date when they left the world and the circumstances under which they became martyrs.

The paintings and posters of the dead on each and every wall were a little disturbing for me. I started to think about how the families of these dead people feel when they have to see the pictures of their dead everywhere and every single day. It was like forcing them to re-experience the pain and distress they once went through. I wondered if they really want their pain to melt away. Do they really want their wounds to be healed? I think they do not want that.

What else could be the reaon for painting graffiti of martyrs and pasting their posters all over the walls, on billboards and over everything possible? It is not just to remember their dead loved ones. It is to strengthen their resilience even in the face of death.

I believe that one of the first things that comes in our minds when we think of a refugee camp is that it would be overpopulated. Crowded streets and neighborhoods. I had the same expectation and image in my mind when I was travelling to Al-Jalazone refugee camp. But to my surprise, the roads were completely deserted. We could see the shop keepers inside their shops and a few locals. It was completely unexpected. I could not understand how this was possible.

I wanted to and was planning to talk to some residents of the refugee camp. There were so many questions in my mind. But my spirit dampened as I walked around the deserted narrow alleys of the refugee camp.

I realized that first-hand experience is quite different from any understanding achieved by reading about a refugee camp and the situations that plague such camps. While walking around the alleys of the refugee camp, we were told that refugee camps still have severe power cut issues. Residents have to do without electricity for several hours every day. There are times when there is no electricity for many days in a row. Other similar problems persist and plague these places.

Something that really unnerved me were the stories of the IDF raids at night in refugee camps.

We were told that IDF raids are so common and routine in the refugee camps that refugee residents would joke around that something has gone wrong and not normal if the IDF soldiers have been absent for more than two or three days.

He narrated his own story and told us that he himself could not complete his studies on time because he was dragged out of his house on many occasions (during his exam days) and beaten and then left battered by the IDF soldiers. He told us that he had spent months in hospital, because of which he could often not sit his exams.

He said,

Refugee camps are very vulnerable and there is no security. Your family is not safe, especially the young boys and the men in the family. They can be picked up and detained for years by the IDF, and there is nothing we can do. No system of law to protect us.

I could see the despair in his eyes. Then suddenly he stopped speaking and smiled. The despair in his eyes gave way to a faint ray of hope when he said, “This is Palestinian life. But we will never give up.” All of us smiled back at him and we continued walking.

I felt so perplexed with the unusual concoction of emotions that stirred up within me when I was touring around different cities and places in West Bank. I was so happy to be there. It was my dream. But the stories of suffering and pain, of tragedy and atrocities, left their mark within me. All my happy moments were laden with heart-rending feelings as well. I felt like a huge box of paradoxes.

We gathered near the bus once again. It was time to leave. I came to the place with many questions. Some were answered, some were not. But I left the place with many more questions.