Overnight, my money was worth nothing!

About two months ago, the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, announced that if anyone is not paying taxes or has black money at home, he or she should come to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to pay the taxes due and a corresponding penalty, but will still have the chance to use some of that “dirty” money afterwards.

Most people did not take him seriously. Two months later, more precisely on 8th November, there was another announcement:

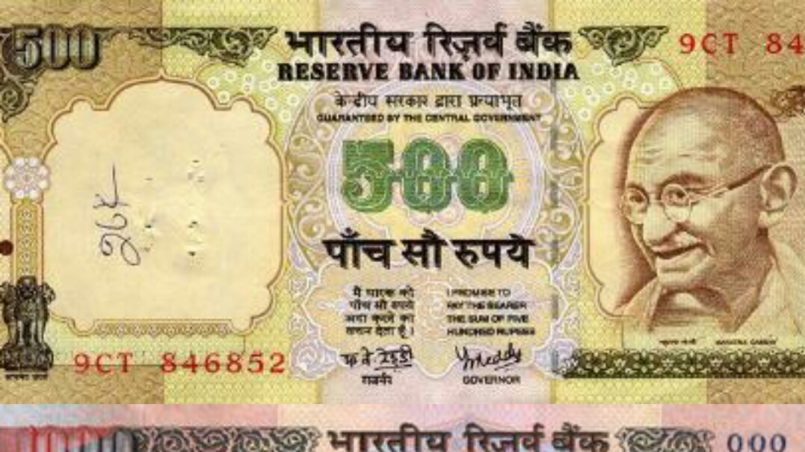

From now on, one person can only exchange up to 4,000 rupee (54.80 €) a day and withdraw only 2,000 rupee (27.40 €) from ATMs. This restriction is due to the scarce availability of the new currency. The people have time until 30th December to exchange their 500 and 1,000 rupee notes.

The turbulence in India’s economic system is evident all over the country and the majority of the middle class and the lower class people do not understand why this is happening because it occurred so suddenly. Furthermore these people are not familiar with the banking system which causes them additional difficulties. For them it means having to find time to sort things out. Time they do not have because they need to work for their money in order to buy food.

All those people who have millions and billions of rupees in their safes, and I am not speaking about white money, no, rather the money which is untraceable and no one knows where it came from and where it is going – their money just turned into useless paper overnight. One day they were rich and the next day they are just in possession of a wad of papers with a number saying 500 or 1000. Kind of ironic, isn’t it?

Through the perspective of a foreigner tourist

On 8th November we were in Pushkar, a small town in Rajasthan, on the edge of the Thar desert in India. We went out to grab something to eat and wanted to pay with a 500 rupee note since that was the only note we had. The cashier said that this money is no longer accepted and I thought he was joking but he insisted that we come back and pay him later with 100 rupee notes.

We went to the next shop and again people were saying the same thing as the previous man, but they were nice enough to offer us the groceries we wanted to buy and told us that we could come back the next day to pay.

We were trapped since we were almost out of currency, we had a total of 700 rupee (9.60 euro) out of which only 200 rupee (2.75 euro) was now acceptable, and most places in India do not accept credit cards. How to pay the guesthouse? How to eat? So many questions were running through my head and the most important was “How can I pay for the train fare?”, since I had to go to South India in order to catch a flight, as my visa was expiring.

We went to every shop in the town but nobody was exchanging 500 rupee notes since it would create additional problems for them, as they would have to go to the bank and exchange them. When we were walking around, we saw a lot of people discussing, arguing, talking and making fun of the current situation.

Eventually we managed to find someone, at a Western Union shop, who swiped credit cards and gave you cash in return but obviously he was taking advantage of the situation and charged us a 12% fee. Additionally he only gave us five 100 rupee notes and the rest were 500 rupees and therefore “useless” at that specific moment.

With that money we could only catch the bus to Jaipur, a big city nearby, and there we hoped to find an ATM. When we arrived in Jaipur, the situation was also critical; many shops were closed, the streets were quite empty – for Indian standards – and at every bank there was a queue of 50 people or more at any time of the day.

Luckily in India women (and also foreigners) are given priority and so we had fast access at the bank. We exchanged our 500 rupee notes but that was not enough and we still had to find a working ATM. That day we must have tried at least 20 different ATMs and many more Western Union branches, but each one of them was either closed, out of service or out of money. At the end of the day, we still didn’t have enough money to buy a train ticket and I started to worry.

Just out of curiosity I put the card in again and entered 2,000 rupees and it worked again. Apparently the limit of 2,000 rupees per day doesn’t apply to international cards. I put in the same amount a third time and people behind me started to complain as they were anxious that the money would run out and they would have to return home empty handed. I stopped and gave them their turn.

When we arrived in South India, in Madurai, the situation was not much different. The banks, ATMs and shops were closed due to the crisis. We interviewed some people about this matter – let’s see their reactions…

Credits

| Image | Title | Author | License |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Banned in India | Sourabh Sharma | CC BY-SA 4.0 |

|

500 & 1000 Rupee notes with subtitles by Sourabh Sharma | Sourabh Sharma | CC BY-SA 4.0 |