To the Other Side of the Sea

They are people. People who should come before borders. It could have been us, it could have been you.

Through this series of articles, I’d like to share the stories of the people I got the chance to meet in refugee camps in Italy and Greece over the past year. I’d like to start a conversation. Raise awareness. Humanise people. Put a face to what we hear in the news. I guess this is the only way I can come close to thanking the never-ending list of people who have touched me and given me more than I’ll ever be able to give to them.

Please share.

To the other side of the sea. From Eritrea to France. H.’S story.

9th of September was similar to a birthday for me.

One year ago, on that day, I visited the refugee hub in Milan Central Station for the first time. And it simply changed me. That day and that first-reception centre for refugees changed me in a way that I can barely explain.

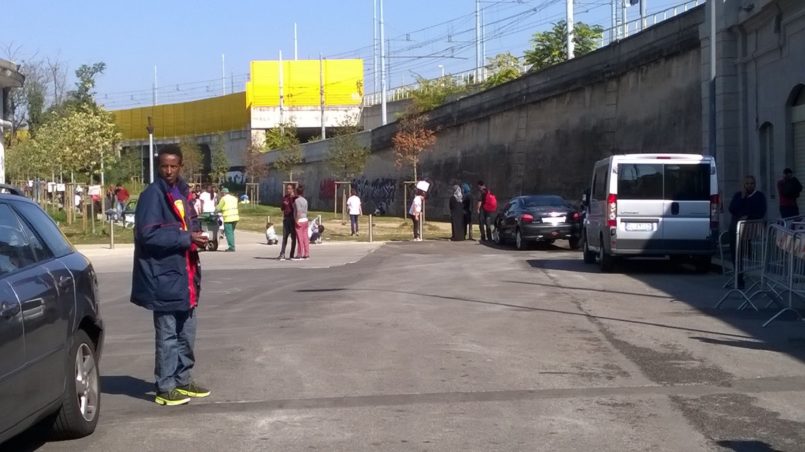

Many things are different now and much has changed since that 9th of September. We have moved from the first hub, based in arches under the railway tracks, to a new and bigger location approximately 2 km from Central Station. A clinic, showers, registration desk, play area for kids, computers to contact those who have been left behind and 75 beds.

The city is linked to southern Italy by trains and buses and at the hub refugees and migrants can find a first-aid area as well as food and clothes before being sent to temporary accommodation. They usually stay for a few days before leaving again. Or, at least, that was before Switzerland, Austria and France started clamping down on migrants.

And regarding Milan, the hub no longer has a first-aid centre. Or better, it has become something else. While I’m writing, volunteers and workers are struggling to squeeze about 670 men, women, kids and even babies into the hub for the night, hitting a new record. Camp beds are not enough.

Around the same time last year, I was becoming familiar with my fluorescent orange vest, the hundreds of cheese sandwiches/glasses of hot tea to prepare and distribute; this September I received a text from a friend. We met at the hub in November, the day he arrived in Milan. He comes from Eritrea and is 23 years old. I’m going to call him J.

J. is in Germany now, waiting for his asylum application to be completed. We’ve been keeping in touch since the day he left Milan, switching in our conversations from English to Tigrinya, German to Italian. And the results of this mixture of languages were not always great, but we always managed to understand each other somehow. The text was similar to others I had received in the last few months. He was asking for help for a friend who had landed a few days before in Sicily, the Italian island which is the main arrival point for refugees who attempt to cross the Mediterranean from Libya.

Ma sweet sis, I want to ask u something if you are ma Lil bro is in milano he came after me

Sariye can you help him if you can… If it is possible

I don’t know anbody else for this

At the end of the text there was a phone number. H.’s number. I called him as I had been told that he was able to speak a bit of English, but the answer to each one of my questions was just “okay, okay”. So I tried to text him, hoping it would be easier for him, and it worked as I finally understood that he was about to leave Catania (Sicily) to be in Milan the next day. I wrote back telling him that I would meet him there.

The following day I went to Milan and I got a text from an unknown number. “I’m H. Please can you call me?” I called and an Eritrean man living in Italy answered me in Italian. He had met H. and his friend at Lampugnano bus station, in the outskirts of Milan outskirts.

Is it okay for you to meet them in Milan Cadorna? I can explain them how to reach it.

Finding H. and his friend in one of the busiest train stations in Milan was somewhat of a challenge. I can’t explain how grateful I was to have a friend of mine, A., with me. Why? Because he could speak Arabic. And guess what? H. had worked in Yemen for some time and could speak Arabic too. It was such a relief for me to know that we could communicate somehow.

I had to explain the situation at the borders to them, as J. told me they desperately wanted to reach France, and the kind of assistance we could give them in Milan. We only knew he was wearing a red t-shirt and that from where he was he could see tram number 9. After 10 minutes of wandering around the station, we finally found H. and his friend A. They were waiting in a quite hidden spot just outside the station, far enough from the soldiers patrolling at the entrance.

One of H.’s first questions was about this:

In Catania they took just one fingerprint. I refused to let them take the other one because I want to go to France. They can’t do anything if they have only one. They have to have two, right?

H. and A. looked incredibly thin and young. Only 17 and 18 years old, and they had made the treacherous journey from Eritrea to Italy completely alone. They had nothing with them, only the clothes they were wearing, a pair of good shoes (and this is absolutely not taken for granted) and an old phone.

We took a jumper with us because we thought we’d probably have to sleep outside

H. said showing us the last of his possessions.

What shocked me the most was that H. was completely different from the Facebook pictures J. had sent me the day before. Almost unrecognizable. It always happens.

I briefly explained to H. and A. how first-reception works in Milan thanks to A.’s translation and we offered to accompany them to the hub for the night. And, again, the main question was about registration and fingerprints.

No fingerprints. Only name and country of origin. It’s for the city to keep track of the number of people and to appropriately organize the assistance

we reassured them.

As soon as we got to the underground, I called Gianluca to make sure they could get a bed and something to eat soon as they were exhausted. Gianluca is one of the people in charge of the hub and works for Fondazione Progetto Arca, an Italian NGO which provides relief to vulnerable groups such as homeless people, families in difficulties, the elderly, refugees and migrants. He is there every single day, from morning to late in the night.

The journey in the underground gave us time to talk. H. and A. started talking and laughing in Arabic, while H.’s friend and I were just staring at them trying to imagine what they were saying. H. wanted to talk and laugh. To come back to life, somehow. We asked them about their journey. From Eritrea to Sudan. From Sudan to Libya. And finally to Italy.

It took them more than a month and several days in the desert to reach Libya, or better migrants’ hell. In Libya, on the migrant route up to the coast, the risk of being taken for ransom is extremely high. According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) there are one million migrants in Libya and an extensive human trafficking network.

They didn’t give us food and they used to beat us with pipes.

Girls and women are repeatedly raped and the eyes of the young girls we welcome at the hub seem to scream this.

H. and A. were able to leave Libya and after one day adrift in the Mediterranean, they were dragged out of a sinking dinghy by the Italian Coast Guard.

We could see sharks

H. said. In Eritrea they were working for the country, which is a sort of hard labour.

Our stop. After 10 minutes walking, we finally reached the hub. The sun started setting and hundreds of people were waiting in line to receive food or in front of buses to be sent to temporary accommodation. Gianluca came towards us and, while shaking hands with H. and A., he kept saying “welcome, welcome”. I can’t even describe how much I love that man! We were told there was space for them in one of the buses, which was heading to a second reception centre (SPRAR).

We only had time for a quick “Stay safe” and “I’ll call you tomorrow”.

The day after both A. and I called H. to make sure they were okay. Communication was still difficult but he was definitely more relaxed. He was finally fine. In the following days we kept in touch and A. went to visit them in the centre. Two weeks ago H. wrote to me saying they were about to leave for Ventimiglia, on the French-Italian border. They wanted to attempt the crossing to France, the last step of their journey to the other side of the sea. A journey through deserts, borders, prisons, kidnappings, ransoms, the deadliest sea.

For seven days we didn’t hear anything from them and H.’s phone was disconnected.

Thank you for sharing this heartbreaking story ♡