Stefan Zweig – An Austrian from Yesterday?

Event data

- Datum

- 12. 6. 2017

- Host

- Kulturverein Wien

- Location

- Hanuschgasse 3, 2. Hof, Stiege 4, 1. Stock

- Event-type

- Vortrag

- Participants

- Dr. Klemens Renoldner, Zweig-Experte

The refugee Stefan Zweig

On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the death of the famous, above all in foreign countries, Austrian author, the Kulturverein invited the Zweig expert Dr. Klemens Renoldner to give a talk in Vienna. He described the time from the escape from Austria until Stefan Zweig’s suicide in Brazilian Petrópolis in 1942. Zweig, who longed for the Austria which existed before the war (meaning the time before World War I), temporally and geographically, was not a monarchist – au contraire: he saw the cosmopolitan Austria as the role model for a European development (similar to the successor to the throne Franz Ferdinand who was murdered in 1914) with all its freedom in culture and society, but also with all its flaws.

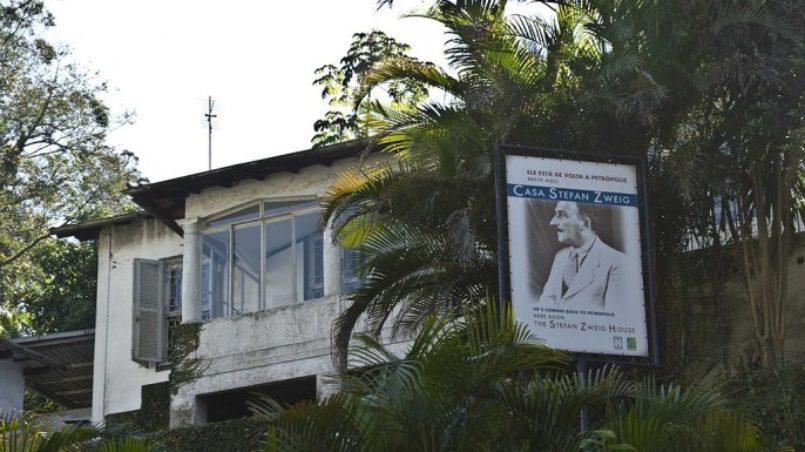

Brazil, which he, also due to his very successful book tour in 1936, chose as his home, could never replace his true homeland Austria. Although he loved the people and the fullness of life which South America offered him, the language barrier (although he spoke five languages, including Spanish, he gave up learning Portuguese after six weeks) as well as the decision for Petrópolis (he could also have stayed in Rio) led to mental and personal isolation. His discussion partners from earlier years (almost exclusively men) were spread around the world due to the escape situation. The only thing he had left was to correspond by letter as he could no longer travel to many countries of the world, even with his English passport.

Hannah Arendt, who deeply hated him, accused him of never stressing his Jewish roots, despite the fact that he occasionally criticised the circumstances in Europe. He found it just as difficult to deal with this polemic criticism as to deal with the reality in Brazil after the publication of his travel book on this country:

The government had led the country to the right and the controlled media reproduced the anti-Semitic rhetoric from Europe, which was also directed at him, who almost saw the country as a paradise and also described it as such.

The movie Farewell to Europe, which highlights Zweig’s time in exile, was, according to Zweig experts, despite many critical voices, superbly made and historically correct, despite many critical voices.

Personal conclusion: history is always current

Zweig’s fate and his detailed description of what it means to be a refugee, is currently highly relevant. He was lucky to be famous and wealthy and to have a large circle of friends and helpers (otherwise he would not have been granted a permanent visa for Brazil).

Moral Europe likes to hold a discussion on whether the reasons for fleeing are economic or military in nature – a discussion which is actually secondary: you can equally die from a bullet as from an empty stomach.

The starting point is much more difficult for the majority of refugees than at the time of Zweig.

On the other hand, many in the domestic population are afraid that, considering the economic situation, they will lose even more between the millstones of globalisation. But it is important to note: it is statistically proven that the downturn of wage income began in the 1980s when the first neoliberals took the reins and lowered corporate and profit taxes to the detriment of labour. Therefore, long before today’s migration wave emerged.

I will end with a question which I have considered for a long time: how do you recognise if a person at the border is a genius or a rapist? Whether he (or she) will become a David Alaba or a gangster boss? Yes, there are many problems and crimes which are currently caused by immigrants. But laws, which have to be executed, exist for these problems (and no: we do not need a tightening, the existing ones have to be evaluated first).

There are many positive examples of successful integration, as we have seen in the Austrian football national team for years.

Therefore, this is the order of the day: support and request. If we examine success models like Canada and build effective plans upon this – plans which can be put up for discussion without right-winged (foreigner = criminal) or left-winged (blaming the opponent of being a Nazi) blinkers – this extremely difficult task can be successful. To achieve this, there has to be a growing willingness from both sides and an open dialogue, free from prejudices and ideologies.

Translation into English: Anna Stockenhuber

Credits

| Image | Title | Author | License |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Casa if Stefan Zweig in Petropolis | Andreas Maislinger | CC BY-SA 3.0 |